Flamenco Guitar Method Volumes 1 & 2 (plus MP3 Pack) by Gerhard Graf-Martinez for teaching and self-study. With sheet music and tablature (TAB). A clear and concise textbook and reference book. Also available as video MP4 download and HD stream - with identical content to the book.

This clear and concise instructional and reference book, declared a standard work by the specialized press, shows every guitarist a safe and viable way into the fascinating world of flamenco.

The code included with the book allows the free download of the MP3 tracks. The audio samples are not only a pure listening pleasure "Flamenco puro", they also convey the necessary, authentic sound and the pulsating rhythm of flamenco, the "compás". Only in this way is a successful self-study at all possible and meaningful.

However, the 92 mp3 tracks can also be purchased separately.

Buy video

Flameno Guitar Vol 1 (en): 16,- EUR

Flameno Guitar Vol 1 (en): 16,- EUR

mp4 movie, HD, file size = 3.0 GB - English

*) mp4 can be played on all devices, smart TV, computer Mac/Win, tablets and smartphones.

There is no right of return or refund for digital products.

Flameno Guitar Vol 2 (en): 16,- EUR

Flameno Guitar Vol 2 (en): 16,- EUR

mp4 movie, HD, file size = 3.0 GB - English

*) mp4 can be played on all devices, smart TV, computer Mac/Win, tablets and smartphones.

There is no right of return or refund for digital products.

Mini pages of vol 1 with audio samples.

Mini pages of vol 2 with audio samples

- Intrumental knowledge of the flamenco guitar

- History of flamenco

- explanations of the different genres and the rhythms

- supplemented by a rich glossary.

This guitar method is for everyone who is interested in the Flamenco guitar and its techniques. The logically structured method may serve as a guideline for everyone who has not found the right teacher or teaching materials yet, for everyone who plays Flamenco guitar, but still has questions about right hand techniques, and for everyone who teaches Flamenco guitar. At the same time, it is a reference book on questions about Flamenco in general. The two volumes contain all aspects I consider important to Flamenco guitar playing: instrumentology, the history of Flamenco, a description of the different styles and their complicated rhythms, and a comprehensive glossary. Notation and tablature are not explained in this book because I assume that everyone knows these facts, as well as the basic techniques of the classical guitar. The tablature includes note values because I think that even tablature readers use them to orient themselves, even if it’s not done consciously.

My many sojourns to Andalusia and my work in Madrid, as well as my friendship and acquaintance with greater and lesser “Maestros,” have influenced my knowledge and experience collected in this method - not forgetting my first inspiration by my long- standing friend and guitarist, Manolo Lohnes, who has contributed considerably to the development of Flamenco in Germany. During 25 years of teaching, I have repeatedly been challenged to think about and analyse what my fingers and, above all, the fingers of the great “Maestros” were doing, and how I could pass on my “experience” and the things I had learned. As everyone else who teaches Flamenco, whether guitar or dance, I was ”made” a teacher by my students. Moreover, I learned a lot from countless performances which took place without rehearsals; in these cases, I was introduced to the dancers and singers in the dressing-room only shortly before the performance. As a man and musician, working together and being on the road, especially with “Gitanos,” has given me, being a “foreign flamenco,” a lot. Thanks to all this and to working with my partner and “bailaora graciosa,” Lela de Fuenteprado, Flamenco has become what it is for me now: “la vida.”

Flamenco is not only guitar music. Although Flamenco gained world-wide popularity because of the guitar or guitarists such as Carlos Montoya and Manitas del Plata in the 1960s and Paco de Lucía in the recent past, its cornerstones still consist of singing, dancing, the guitar, and the “jaleos.”

Flamenco is a very emotional, yet rigid form of art and an attitude about life. Flamenco means spontaneity and improvisation in music and in life: to live “now,” not to give oneself up, despite desperate straits, to overcome mental and physical distress without aggression, by using music and dance as an outlet, to accept one’s fate, to make the best of every situation, however little that may be - and to do all this with an enormous zest for life and a strong will to live.

This might be the reason why Flamenco is one of the most elemental forms of music making and dancing which exists strongly from “listening to oneself.”

However, this method can at best serve only as the grammar and vocabulary of the Flamenco “language.” You should learn the subtleties and wealth of this “language” where it is spoken. Since this is not always possible, you should at least have a good look at Flamenco music, i.e. listen to records, go to concerts and try to come into contact with Flamenco artists, especially Flamenco dancing schools which can be found in every major city now.

As there have been virtually no pedagogically trained Flamenco teachers to this day, the music has always only been passed on orally. Only recently have people begun to transcribe it. Moreover, Flamenco was never composed, either. If there are arrange- ments, they leave much room for improvisation, i.e. free access to the countless “drawers” of a large “chest of drawers.” But someone did create the contents of the “drawer,” the “falseta,” some time and did learn and practise the form of the “chest of drawers,” i.e. the genre with its fixed rhythms and rules.

This guitar method is structured according to these principles. There are no complex compositions. I deliberately refrained from combining the exercises, rhythms and variations, but rather adapted them to the technical requirements and levels. My aim is to motivate the student to learn those individual parts, or “drawers,” by heart in order to combine them freely, but without exchanging the “drawers” for those of a different “chest of drawers,” or to apply the form of a different “chest of drawers.”

It is essential to follow the explanations of the techniques and the pictures which go with them very carefully, to achieve the typical sound of the Flamenco stroke, which is the main point in this book. If the practice pieces on the CD sound better than your own playing, it is not because of my guitar or the recording technique, but solely because of the stroke and the tone production. Listen to the examples on the CD as often as possible to get a feeling for phrasing, articulation and tone production.

I hope you enjoy this book and I wish you every success with the Flamenco guitar.

Sheet music and TAB

Preface

The Author

Lesson 1

Posture

The Sound of the Flamenco Guitar

Fingerlabelling

Rasgueado

One-Finger-Rasgueo

3-Finger-Rasgueo

4-Finger-Rasgueo

Continuing Rasgueo

Lesson 2

Pulgar

Pulgar and ima-Downstroke

Pulgar and Rasgueo

Remate

Pulgar-Downstroke

Ayudado

Lesson 3

Golpe

Golpeador

i- and p-Downstroke with Golpe

m-Golpe with Downstroke

The Rumba-Stroke

Lesson 4

Tresillos

a-m-i-p-Rasgueo

Lesson 5

La Guitarra Flamenca

Guitarreros

Guitarreros actual

La Cejilla

Guitarristas

Guitarristas actual

Uñas

Palmas

Compás

Modo Dórico - Harmony and chords

Sencillos I (Tangos)

Sencillos I (vereinfachte Notation)

Estudio por Soleá

Sencillos II (Tangos)

Naino I (Tangos)

Naino II (Tangos)

Naino III (Tangos)

Naino IV (Tangos)

Soleá-Remate

Mantón I (Soleá)

Caí I (Alegrías en Do)

Ayudado Übung I

Ayudado Übung II

Rumbita (Rumba)

Mantón II (Soleá)

i-Abschlag mit Golpe (Garrotín)

p-Abschlag mit Golpe und p-Abschlag

(Garrotín)

Naino IV (Tangos)

m-Golpe

a-Golpe

Quejío I (Taranto)

Rumba-Compás I

Rumba-Compás II

Rumba-Compás III

Rumba-Compás IV

Rumba-Compás V

Rumba-Compás VI

Tresillo I

Tresillo II

Tresillo III

Tresillo IV

Tangos-Compás mit Tresillos

Soleá-Compás mit Tresillos I

Soleá-Compás mit Tresillos II

Soleá-Compás mit Tresillos III

Soleá-Compás mit Tresillos IV

Fandango de Huelva (Intro)

Fandango de Huelva (Copla)

Sevillanas (Intro)

Sevillanas

Paso Lento (Alegría)

Mantón III (Soleá)

Lesson 6

Arpegio

Tremolo

Lesson 7

Picado

Scales

Lesson 8

Bulerías I

Lesson 9

Alzapúa

Lesson 10

Soleá

Alegrías

Bulerías II

Tarantos

Tangos

Estilos

History

Introduction

Antiquity

Middle Ages

The Moors

The Reconquista

The Jews

The Inquisition

The Conquista

The Gipsies

Terminology

Development of Flamenco

Flamenco in the 50s and Today

Los Tablaos

El Cante - El Baile - El Toque

Pasión

Estilos

Bibliography

Epilogue

CD Tracks

Index

Tracks Vol II

Quejío II (Taranto)

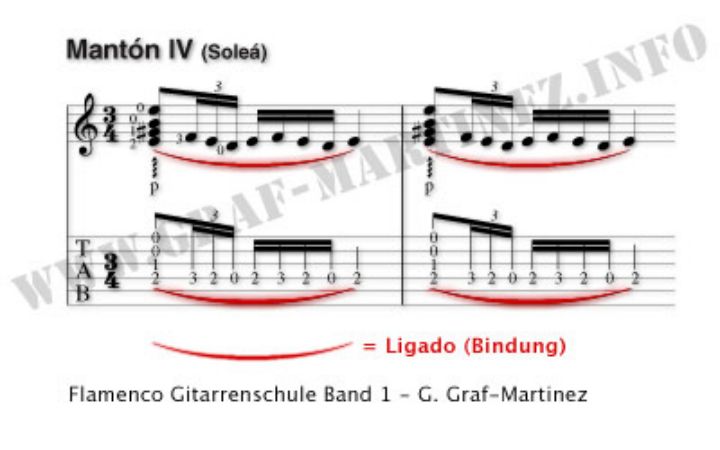

Mantón IV (Soleá)

Mantón V (Soleá)

Mantón VI (Soleá)

Rumbita II (Rumba)

Tremolo Exercise I

Tremolo Exercise II

Quejío III (Taranto)

Picado Exercise I - III

Mi-Dórico

La-Dórico

Si-Dórico

Fa#-Dórico

Lérida (Garrotin)

Compás Exercise I-IV (Bulerías)

Bulerías-Compás I - XVIII

Columpio I - III(Bulerías)

Mantón VIII (Soleá)

Mantón IX (Soleá)

Mantón X (Soleá)

Mantón XI (Soleá)

Alegría en Mi I (Compás Exercise)

Alegría en Mi II (Compás Exercise)

Alegría en Mi III (Intro)

Alegría en Mi IV (Escobilla)

Alegría en Mi V (Puente)

Caí II (Alegría en Do)

Caí III - V (Alegría en Do)

Columpio IV (Bulerías Intro)

Columpio V (Bulerías)

Quejío IV (Taranto)

Naino VI (Tangos)

Naino VII (Tangos)

Naino VIII (Tangos

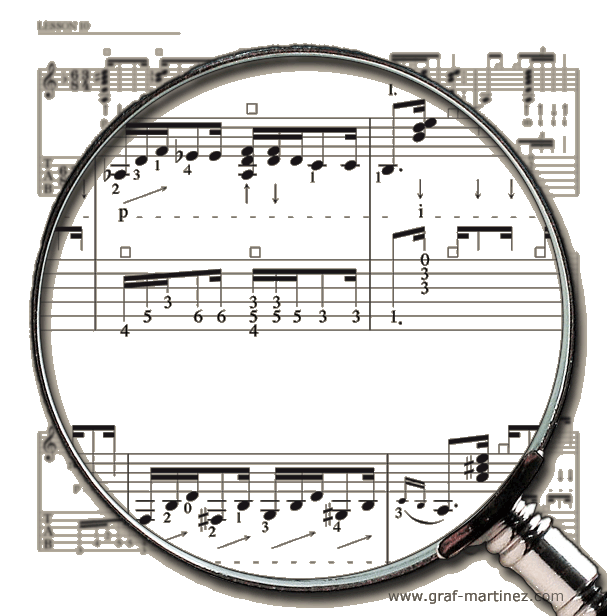

All exercises and compositions in the School for Flamenco Guitar are presented in sheet music and rhythmized tablature, also called TAB, or tabs.

The traditional posture of the Flamenco guitarist is ideal for your back and spine (see picture 1.7). The guitar rests against the upper part of the body and is held tightly between thigh and upper arm. Do not support the guitar at any other points. Certainly not with your left hand (picture 1.6). Your thighs should be horizontal, your seat at knee level or, better, below your knee. Unfortunately, ....

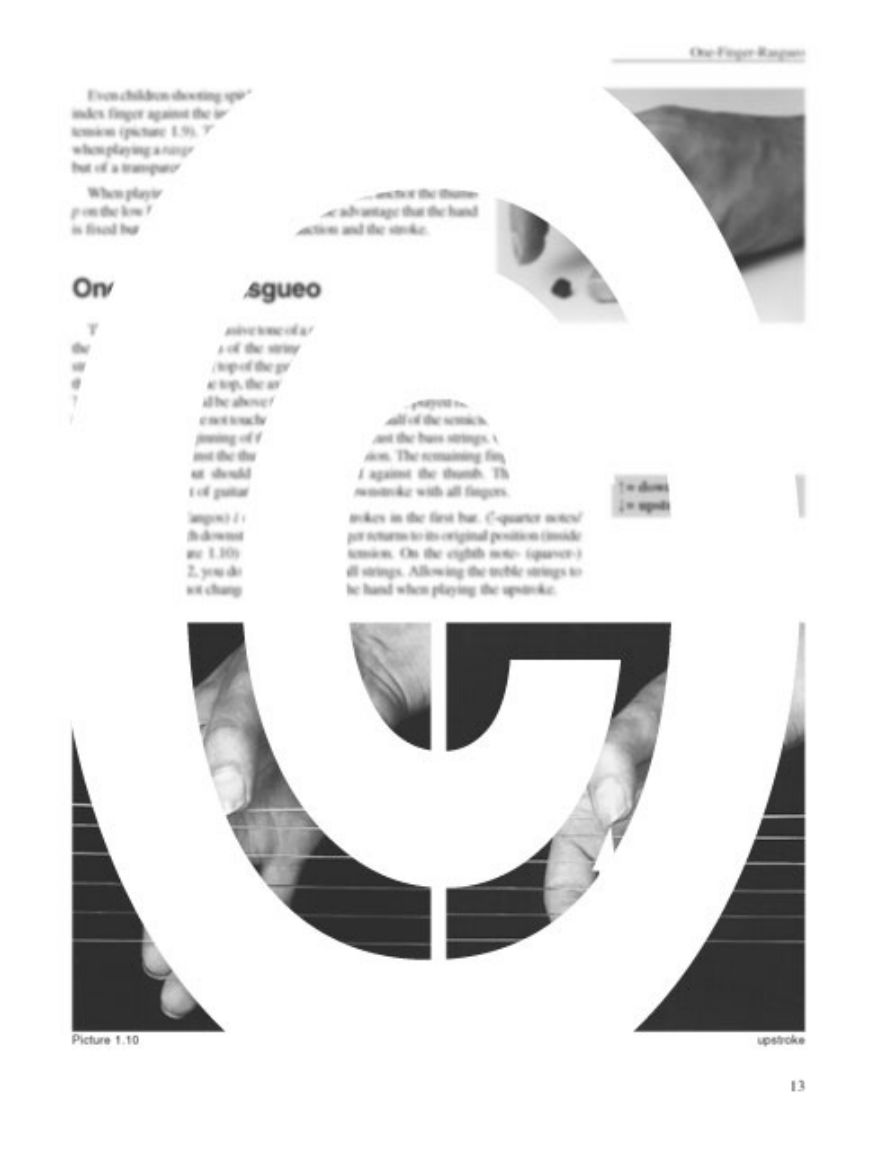

The reason for the percussive tone of a good sounding rasgueo is not the extremely low action of the strings, but because the strings are struck towards the tapa ( top of the guitar). The face of the index fingernail should strike the strings ... (read more in the Flamenco Guitar Method)

.... Only the index finger is pressed against the thumb to build up tension. The remaining fingers may join in the movement but should never be pressed against the thumb. This gives the impression that a lot of guitarists execute the downstroke with all fingers ...

The downstroke and upstroke with the fingers can be combined in countless ways, and there are two different kinds of rasgueos: the finger rasgueo and the hand rasgueo. The most important thing about the finger rasgueo is building up a short tension in the fingers and then flicking them off immediately. In the past, the 5-finger rasgueo was still in use (q-a-m-i or q-a-m-i-p) whereas today, the 3-finger rasgueo is most commonly used. The less fingers are involved in playing a rasgueo, the more difficult it gets to keep the intervals between the fingers. The result should always be a definable and transparent rasgueo. ?Strumming? is frowned upon nowadays. Again, the thumb is placed, or rather anchored, on 6 and is bent. The basic position is the same as that of the one-finger ....

See also the techniques of the great flamenco guitar players

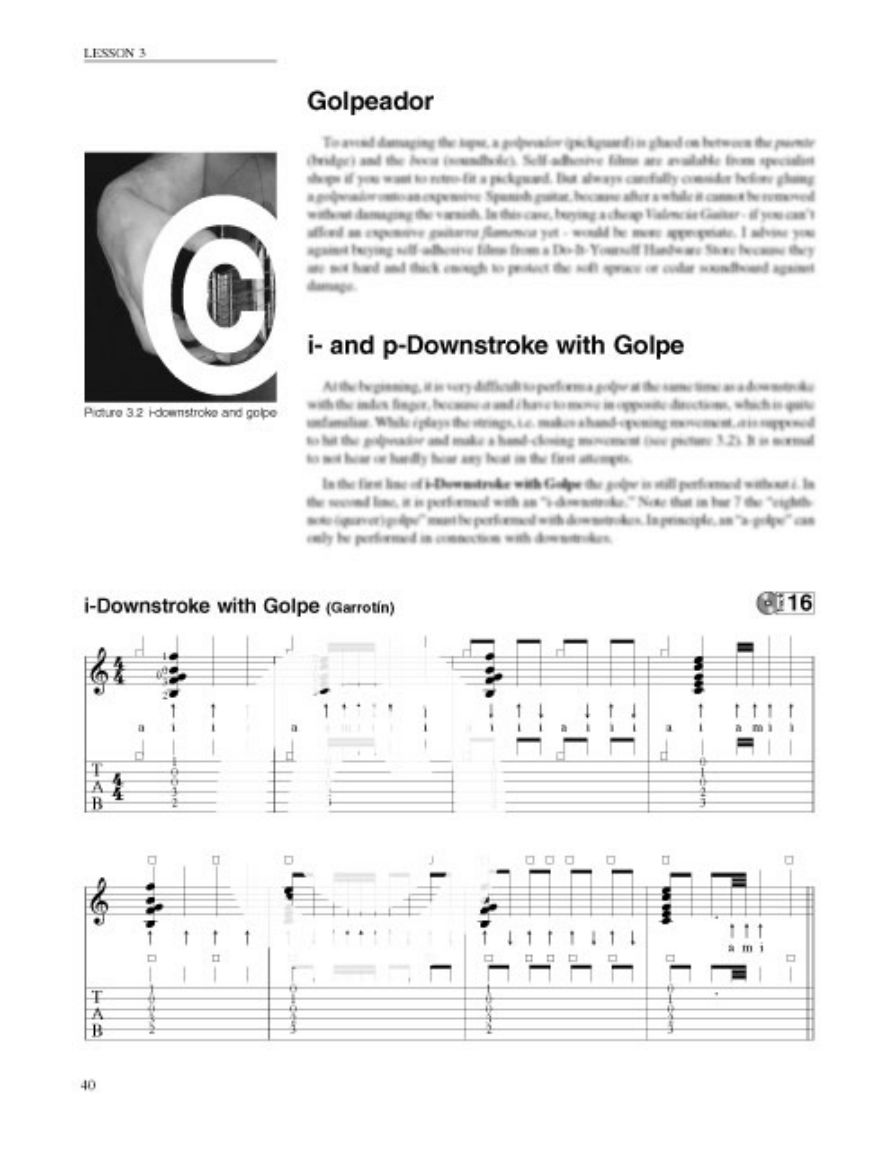

Flamenco Guitar Method - Lesson 3

To avoid damaging the tapa, a golpeador (pickguard) is glued on between the puente (bridge) and the boca (soundhole). Self-adhesive films are available from specialist shops if you want to retro-fit a pickguard. But always carefully consider ...

At the beginning, it is very difficult to perform a golpe at the same time as a downstroke with the index finger, because a and i have to move in opposite directions, which is quite unfamiliar. While i plays the strings, i.e.

Flamenco guitar method: Lesson 4

All 3-finger rasgueos are called tresillos (triplets) in Flamenco, erroneously including rasgueos which are not notated as triplets. One of these tresillos, the rasgueo ...

... No rasgueo is played in so many different ways as the tresillos. On closer examination, all of them are consistent and justified. On the one hand, they were created for reasons of sound or lack of velocity and on the other hand because of physical disabilities. Many tocaors - some of them famous people - who were missing one or even two fingers of the right hand or who were paralysed, created a new rasgueo out of necessity. Also, some guitarists invented different rasgueos or fingerings to ...

Guitar maker

Flamenco guitar method - lesson 5:

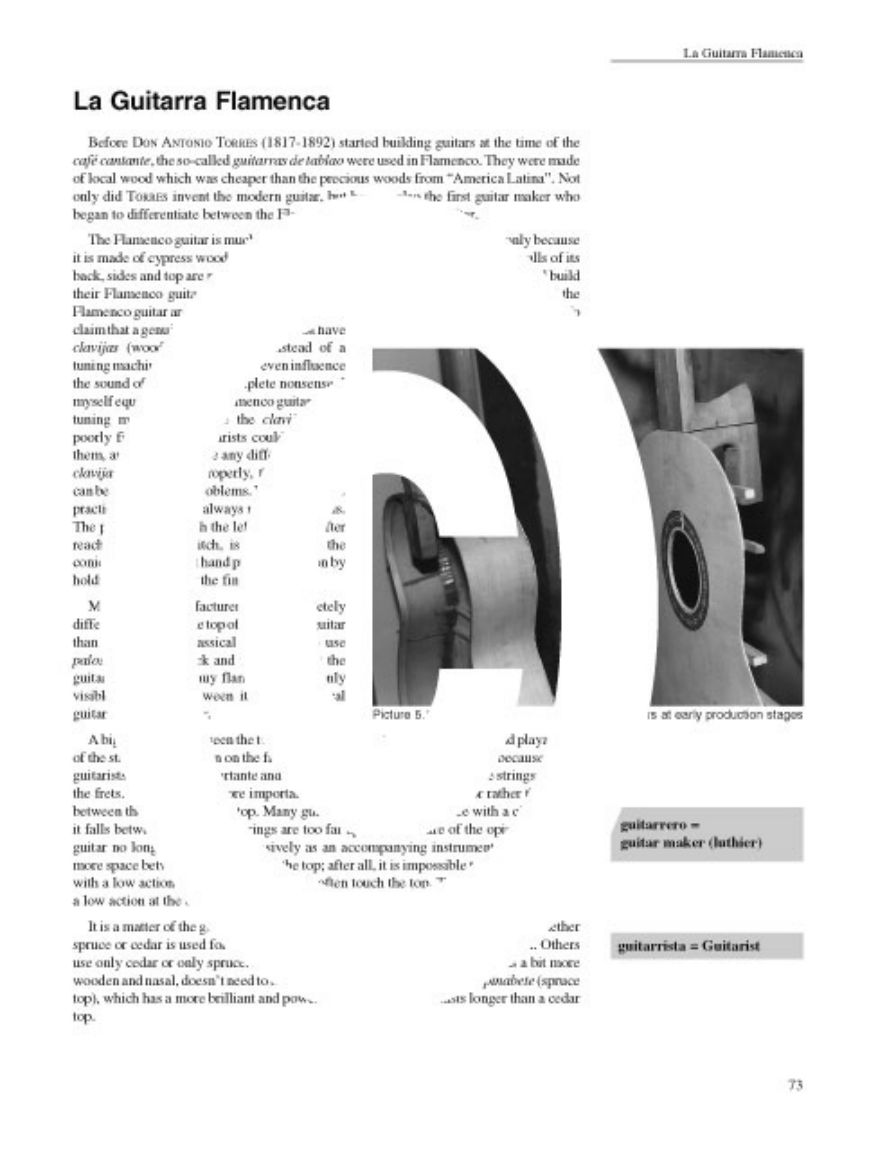

Before DON ANTONIO TORRES (1817-1892) started building guitars at the time of the café cantante, the so-called guitarras de tablao were used in Flamenco. They were made of local wood which was cheaper than the precious woods from "America Latina". Not only did TORRES invent the modern guitar, but he was also the first guitar maker who began to differentiate between the Flamenco and the classical guitar.

The Flamenco guitar is much lighter than the classical guitar. That is not only because it is made of cypress wood, but also, as mentioned in Lesson 1, because the walls ...

Flamenco Guitar Method Vol 2, Lesson 6:

When playing arpegio (arpeggio) the thumb is always played apoyando, unless the ...

Arpegio Exercises Iand II should also be practised with p-m-i-a, p-m-a-i, p-a-i-m and p-i-a-mas well as with i-p-m-a and a-p-m-i.

Flamenco Guitar Method: Lesson 6

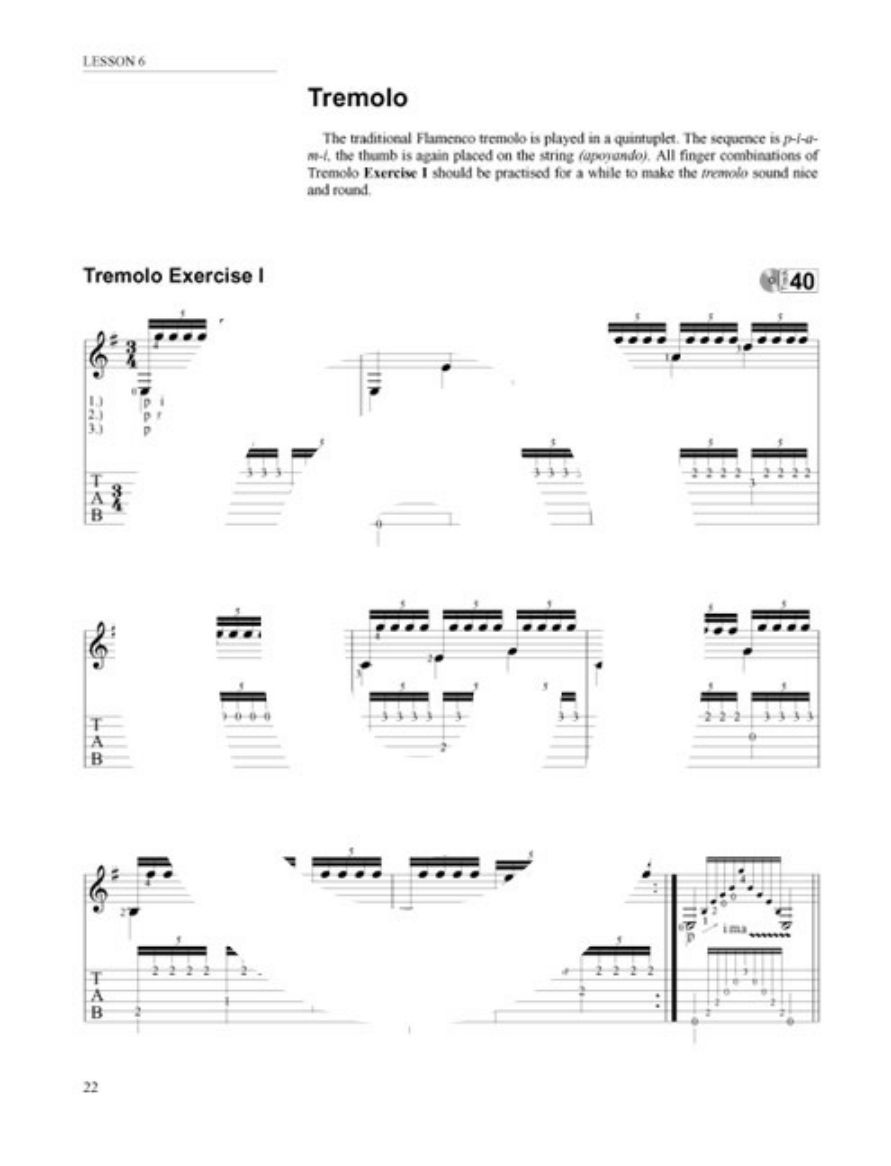

The traditional Flamenco tremolo is played in a quintuplet. The sequence is p-i-am-i, the thumb is again placed on the string (apoyando). All finger combinations of Tremolo Exercise I should be practised for a while to make the tremolo sound nice and round.

PACO DE LUCÍA'S picado technique has become a standard technique of the young tocaores. The old master SABICAS used it as well, but PACO DE LUCIA´s picado was even more sparkling and brilliant, and he played it with incredible velocity. The brilliance and velocity are achieved merely by the postion of the hand. In this technique, the thumb is always ...

This stroke creates the typical Flamenco picado which has become a standard.

See also the techniques of great guitar players

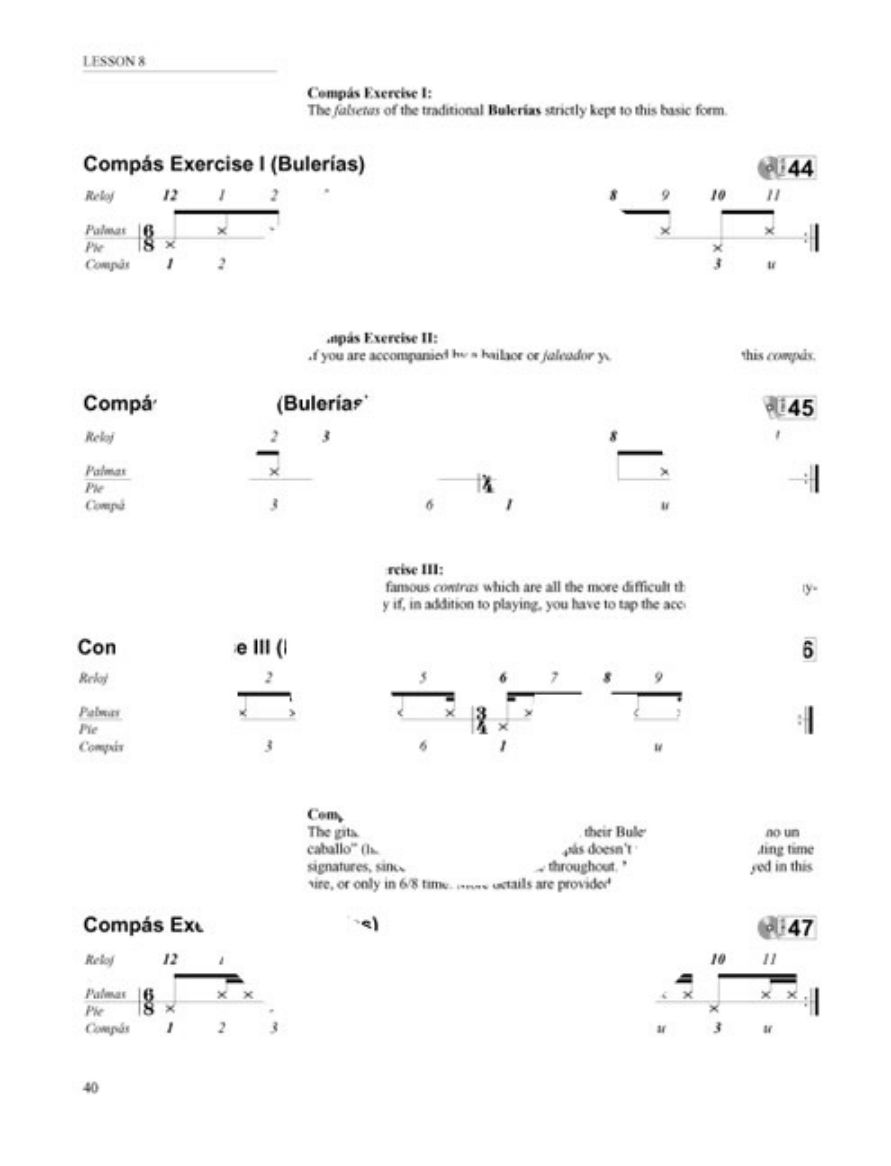

The Bulerías belong to the most popular toques, especially for the young guitarists, because compás security and virtuosity can be shown to their best advantage. Experience shows that if you fully understand the compás of the Bulerías and its va- riations, you will find the rhythms of the other estilos, played according to the 12-beat compás, easier. Even though some guitarists play them very gently or “academically, ”the Bulería is and will always be the Flamenco style which is played very powerfully, especially by the gitanos. Not only in toque, but also in cante and baile. Whereas solos are mostly played in “La-dórico,” you will find all kinds of modes in the acompañamiento To a good tocaor ...

Flamenco Guitar Method, Vol 2:

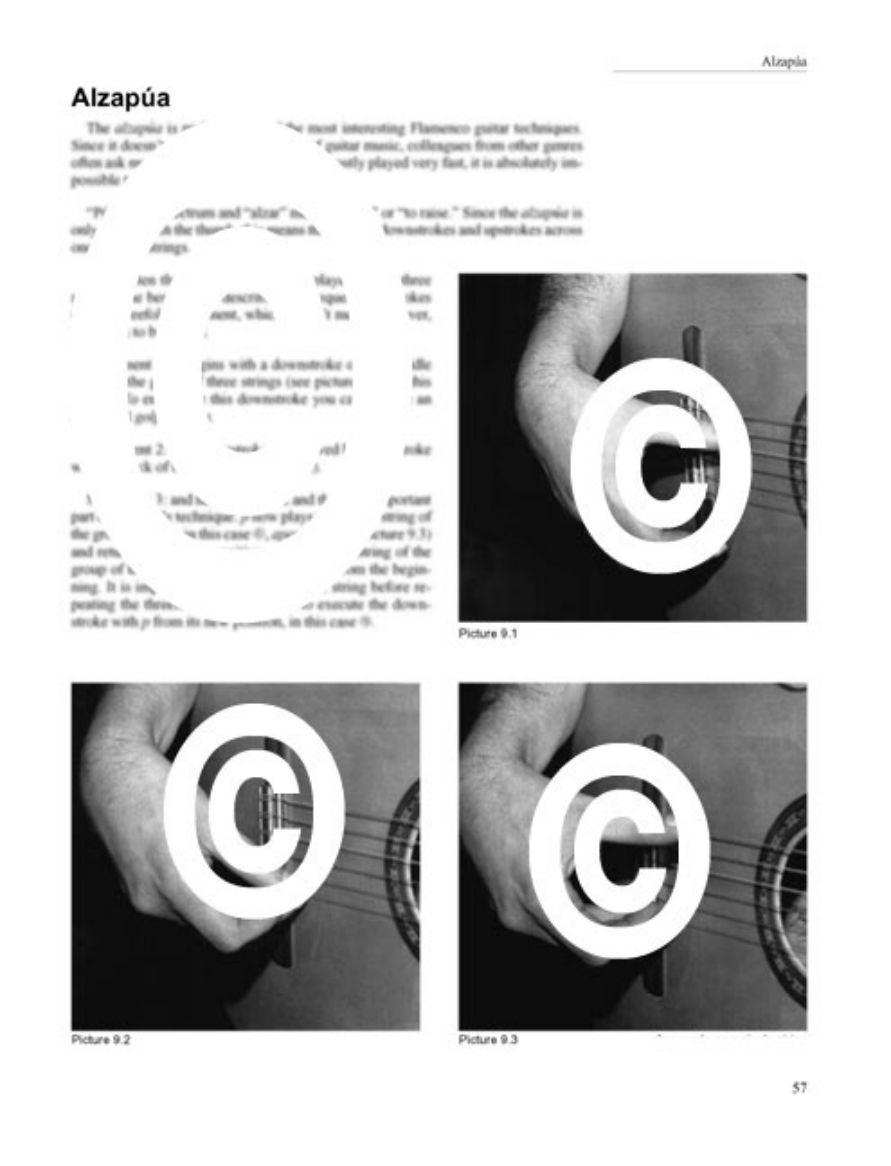

The alzapúa is probably one of the most interesting Flamenco guitar techniques. Since it doesn't exist in any other kind of guitar music, colleagues from other genres often ask me how it works. And since it is mostly played very fast, it is absolutely impossible to see the sequence of strokes.

"Púa" is the plectrum and "alzar" means "to lift" or "to raise." Since the alzapúa is only played with the thumb, this means that p plays downstrokes and upstrokes across one or more strings.

More often than not, the alzapúa is played across three strings. The best way of describing the sequence of strokes is as a threefold movement, which doesn't mean, however, that it has to be a triad.

Movement 1: p begins with a ...

See also the techniques of treat flamenco guitar players

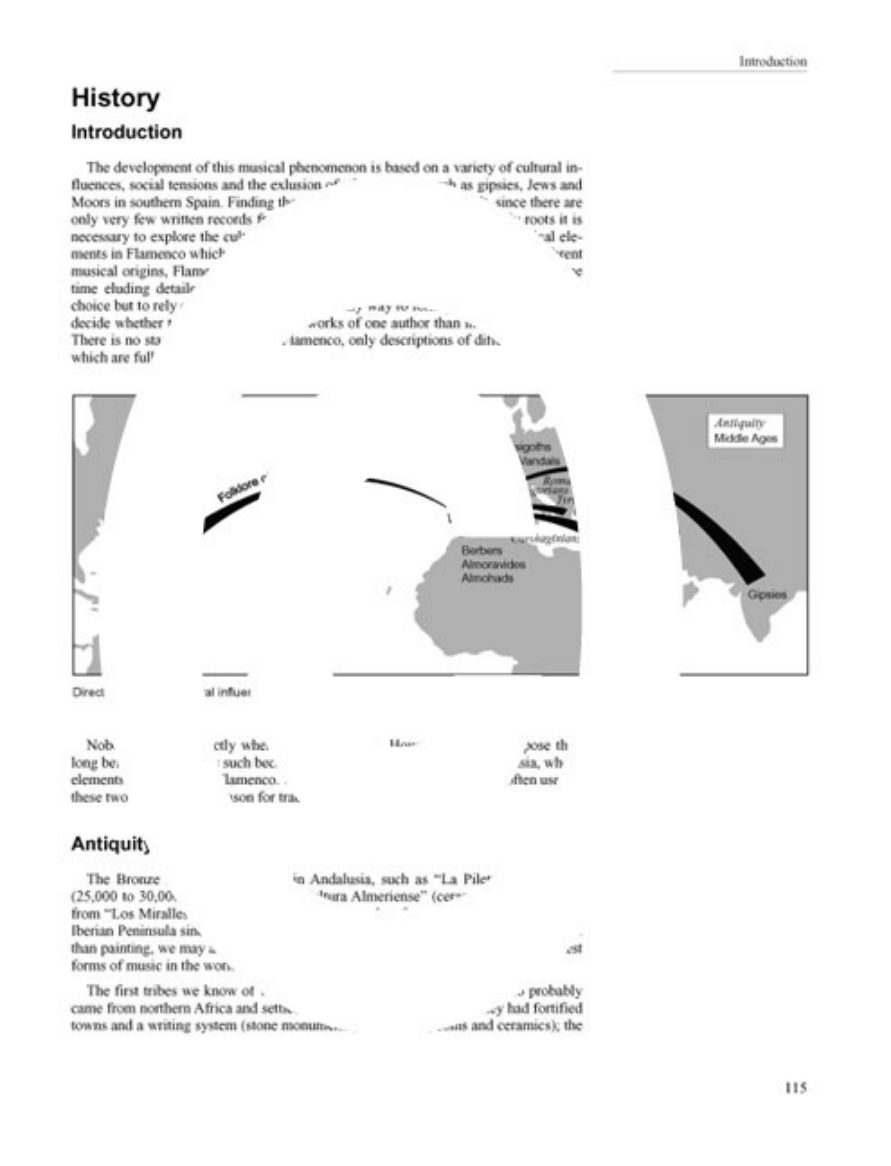

The development of this musical phenomenon is based on a variety of cultural influences, social tensions and the exlusion of ethnic groups such as gipsies, Jews and Moors in southern Spain. Finding the origins of Flamenco is difficult, since there are only very few written records from past centuries. To investigate its early roots it is necessary to explore the cultural history of Andalusia and the different musical elements in Flamenco which point to its varied origins. Thanks to this blend of different musical origins, Flamenco has become what it is today: fascinating and at the same time eluding detailed analysis. Even flamencologists often disagree and have no choice but to rely on guesswork. Often, the only way to form your own opinion is to decide whether to believe more in the works of one author than in those of another. There is no standard theory about Flamenco, only descriptions of different opinions ...

The Bronze Age cave paintings in Andalusia, such as "La Pileta" near Ronda (25,000 to 30,000 years old), or the "Cultura Almeriense" (ceramic and copper art) from "Los Miralles" near Almería, prove that works of art have been created ...

After the decline of power of the West-Roman Empire (from about 400 A.D.) the Vandals (an East-Germanic tribe) passed through and looted Spain. However, after a short time they were driven to North Africa by the Visigoths where they established ...

In 711 A.D. seven thousand Berbers led by the Arab commander and governor of Tanger, TARIK IBU ZAYAD, crossed the Strait of Gibraltar. The moros were allegedly ...

The Reconquest, i.e. the reconquering of Spain from the Moors, and the Conquista, i.e. the conquest of America, began in 1492 and are still celebrated as national events today. The Reconquest began as early ... (read more in: Flamenco Guitar Method by Gerhard Graf-Martinez, Vol 2, lesson 10.)Here are the four most important scales in the Flamenco mode. This mode is called modo dórico. The notes with an accidental in parentheses are only played on the basic chord (the dominant). See Volume I, Modo Dórico.

As mentioned before, the Jewish epoch began long before the Christian era. This allegation is substantiated by the fact that, in Christ's day, Jewish pilgrims called sephardim came from Spain to Jerusalem. Sepharad (the biblical term) denoted ...

When FERDINAND and ISABELLA, Kings of Castile, decided to clean Spain of minorities in an endeavour for racial purity and religious unity (Catholicism being the only religion), a sad process began, depriving Spain of some of the important representatives of its cultural, economic and ...

The Conquista (conquest) was the epoch in which Spain rose to world power because of its conquest of the New World and other countries. The famous conquistadores, CORTEZ and PIZARRO, conquered ...

India is the presumed country of origin of the gipsies. However, to date, researchers have not been able to prove whether they came from the valleys of the Indus (more than three thousand kilometres long) or Rajasthan (a state bordering Pakistan) or the Hindukusch mountains. And it is not quite clear, either, why they left their ... (read more in: Flamenco Guitar Method by Gerhard Graf-Martinez, Vol 2, lesson 10)

Question: In the first flamenco book, in the second lesson, in Mantón 1, there are a few pulgar strokes on the d-string right at the beginning. On the CD, the strokes are pretty fast, are they really just played one after the other with the thumb, or is there another trick? Because they are really pretty fast! Or is that just practice?

The 16th notes are not played with p or with a trick. It is a so called ligado (binding with the left hand). *)

*) Quotation from the preface of my Flamenco Guitar Method: Explanations of notation and tablature have been omitted, since these, as well as the basic techniques of the classical guitar are assumed.

Lessons

Site Owner

Gerhard Graf-Martinez

Theodor-Baeuerle-Weg 9

73660 Urbach

Fon +49 (0)7181 480 90 25

Imprint | Privacy policy

© Copyright 1995 - 2022 · Gerhard Graf-Martinez